Last year in the Bay of Biscay, a salvage team from SMIT Salvage completed a spectacular rescue operation that generated intense global interest. Fighting against time and the elements to prevent an environmental disaster, SMIT Salvage towed off the Modern Express car carrier before it would ground at Biarritz on the French coast. Members of the salvage team look back on a successful mission accomplished.

Tuesday, 26 January

The 164-meter-long Modern Express car carrier is carrying a cargo of sawn timber, used equipment and excavators from Gabon in West Africa to the French port of Le Havre. In the Bay of Biscay, 200 miles west of La Rochelle, the ship sends out a distress call. The weather conditions are extremely bad and the 22 crew members are in danger. The ship is listing 40 degrees. The distress signal is picked up by the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) in Great Britain, which passes it on from Falmouth to the Spanish MRCC officials, who go into action immediately, sending two search and rescue helicopters to the ship. All the crew members are evacuated unharmed.

On alert 24/7

The distress signal is also picked up by the Global Maritime Distress & Safety System of the operational department of SMIT Salvage in Papendrecht, which is on the alert 24/7. “Our computer system not only provides us with lightning-fast, real-time information about the ship in question, it also shows which ships are in the area,” says Thijs van der Jagt, Operations Director of SMIT Salvage. “The system also provides information about where we have tugs or auxiliary material in ports nearby. After receiving a call, we immediately contact the owners and insurers of the ship to offer our services. We activate our agents and representatives in the region and inform our own salvage crew members so they can go into action immediately.”

The ship’s engines and electrical systems were down and so all you could hear was the sound of the ship wallowing in the waves.

Fast decisions

All these procedures were launched on 26 January. “When the message came in from the Modern Express, we knew that the ship was in danger of capsizing,” explains Thijs. “At that point we had to make a fast assessment: does it make sense to mobilize even though there is a risk that all our efforts may be in vain? In this case, we decided to launch an immediate Emergency Response operation.” That decision meant that the operational management, in consultation with salvage master Chris Bos, set up a provisional team. The operational department mobilized ships and salvage material, chartered a plane, booked hotel rooms, and established contacts with the authorities.

Immediate action

The salvage master is the lynchpin in every salvage operation. He has wide-ranging maritime, logistical and nautical expertise and experience. As the head of operations, the salvage master is closely involved in setting up the salvage team and he runs the team during operations. Chris is one of the fifteen salvage masters at SMIT Salvage. “We always have a suitcase with clothes, toiletries and personal protection equipment in our cars,” says Chris. “It contains a life vest, a helmet, gloves, overalls and boots, but also gas meters and a range of communication gear. We know the phone can go any time and then we have to act without a moment’s delay. We can sometimes be on a plane an hour after a distress call comes in.”

Climbing exercises

In the meantime, the MRCCs had decided to coordinate the rescue operation from the French Prefecture Maritime in Brest. That same evening, a first response team led by Chris leaves for Brest. The team includes assistant salvage master Johan Spaans, naval architect Roy Riethof, a superintendent, a supervisor, a shore coordinator and four salvage divers. “We knew the ship was listing 40 degrees,” says Chris. “So we needed our climbing gear. Our colleagues are trained by professional climbers and we had just completed an intensive course. When we arrived at the hotel in the evening, our team did some climbing exercises to prepare for the tough job waiting for them.”

Wednesday, 27 January

At a speed of three knots per hour, the Modern Express is drifting towards the French coast. SMIT Salvage signs an LOF SCOPIC salvage contract (see inset) with the ship owners to take the vessel in a safe condition to a safe location. Chris, Johan and Roy go to the Prefecture in Brest. A helicopter is chartered immediately to take Chris to the Modern Express, where he assesses the situation. “As I circled over her, I could see that she was sometimes listing almost 50 degrees,” he says. Back in Brest, Johan and Roy are starting up the onshore operation. They send casualty information sheets to the ship owner with a request for as much information as possible about the ship and the cargo. With that information and the weather forecast, Roy can use dedicated 3D software to calculate, visualize and simulate the risks.

Puzzle

Johan: “In terms of logistics and communication, the onshore team had a really challenging job to complete in a short time. We mobilize people, equipment and material, and coordinate with a wide range of stakeholders such as representatives from insurance companies and government authorities. That means solving a complex puzzle very quickly. In this case, the events were also being widely reported in the media, and so there was a continuous flow of requests for information.”

Thursday, 28 January

The French authorities send in the Emergency Towing Vessel (ETV) Abeille Bourbon and the frigate Primauguet, which has a Lynx helicopter. The weather is still bad. As feverish preparations for a salvage operation continue in Brest, the Modern Express drifts further towards the French coast, with several hundred tons of heavy oil, diesel and lubricants on board. To prevent an environmental disaster, the French authorities keep the AHTS (Anchor Handling Tug Supply vessel) Argonaute, with anti-pollution equipment, on standby. Two tugs mobilized by the salvage team, the Centaurus and the Ria de Vigo, arrive at the Modern Express. The helicopter takes Chris and salvage diver Vincent Koning to the frigate and then they switch to the Centaurus. They circle around the Modern Express for hours, studying the ship’s behavior and plan ways of boarding. In view of the strong winds and high waves, there is no permission from the authorities to go ahead to attempt to board the casualty.

Friday, 29 January

Wind force 9. The Modern Express is now 150 miles west of La Rochelle. The insurers send a special casualty representative to Brest to monitor the salvage team’s progress. The offshore team is working on preparations to tow the ship. It is impossible to right the ship on the high seas, especially in this weather, so it will have to be taken to a port while listing. Negotiations proceed with the port authorities to decide on a port of refuge. During the morning, a four-man salvage team gets the green light from the French authorities to board, preceded by a member of the French emergency services. Team member Peter van Olphen recalls: “We left Brest in a helicopter fitted out with a special winching kit for lifting and lowering people. It was too big to land on the frigate and so it had to take on extra fuel for the return flight. Once we got to the Modern Express, the pilot managed, despite the strong winds, to lower us one by one to the ship’s deck on a cable attached to the harnesses that we wear. Our French colleague’s task was completed once we were on board. He was picked up and went back to shore on the helicopter.”

Listening

Team member Peter Smits: “The ship’s engines and electrical systems were down and so all you could hear was the sound of the ship wallowing in the waves. We studied the ship’s drawings, but we didn’t know exactly what was going on with the cargo. If a cargo moves, that can affect the stability of a vessel and so we tried to pinpoint and interpret the sounds. Was the thumping coming from one of the holds, or was it caused by something else? You try to find an explanation for what you are hearing. Then the real work begins: establishing a towing connection as quickly and safely as possible to tow the vessel away from the shore.” Team member Peter van Olphen adds: “We had been dropped near the bridge but we had to move three decks down to establish the towing connection. It’s like being in a large office building that is tilting right over and having to get to the ground floor from the third floor. You can only use the railings in the staircases so it’s a question of climbing down. With the ship listing between 15 and 40 degrees or more we tied ropes to the rails to prevent falls and we were in constant radio contact with Chris, who was directing us from the Centaurus.” Once they reach the bows on the right deck, the team goes to work. A thin line tied to a heavier cable is shot over from the Centaurus to the Modern Express and so, in the end, the team finally has a large steel cable on board. The sea state makes it impossible for the team to get the cable around a bollard. In the meantime, it is getting dark and the Lynx helicopter takes the team off board.

Working safely is an absolute priority for us, however spectacular our work sometimes looks.

Saturday, 30 January

The Modern Express is drifting further south in six-meter-high waves. She is just 120 miles offshore. The salvage team goes on board a second time, this time to complete the preparations for the towing connection. A helicopter delivers a 150-meter-long, flexible, Dyneema towing line, which has been brought in from the Netherlands by courier, on board the Ria de Vigo, which will later transfer the 1,000-kg line to the Centaurus.

Sunday, 31 January

The storm is so violent that it is now impossible to go on board. The Centaurus, which has to bunker, leaves for the Spanish coast, a 12-hour voyage. Chris and Vincent stay on board to discuss the next steps with the authorities and local agents. When another attempt to establish a connection fails, the French government announces that the Modern Express may run aground. At the end of the day, the ship is just 50 miles west of the coastal resort of Arcachon. The salvage team prepares for the final attempt to save the ship. The Centaurus returns from Spain that evening with the aim of making a final throw of the dice the next morning.

Monday, 1 February

In slightly better weather, the helicopter takes the team on board again at half past eight in the morning. Forty-five minutes later, they arrive at the bow of the ship. This time, they manage to connect the Modern Express to the Centaurus with the Dyneema line. The ship is now just 26 miles away from grounding. The helicopter picks up the team members and the Centaurus can start towing the listing vessel to Bilbao, the port of refuge selected by the Spanish Government for righting the Modern Express. The SMIT Salvage onshore team gets on a plane to Bilbao to continue with the job.

Tuesday, 2 February

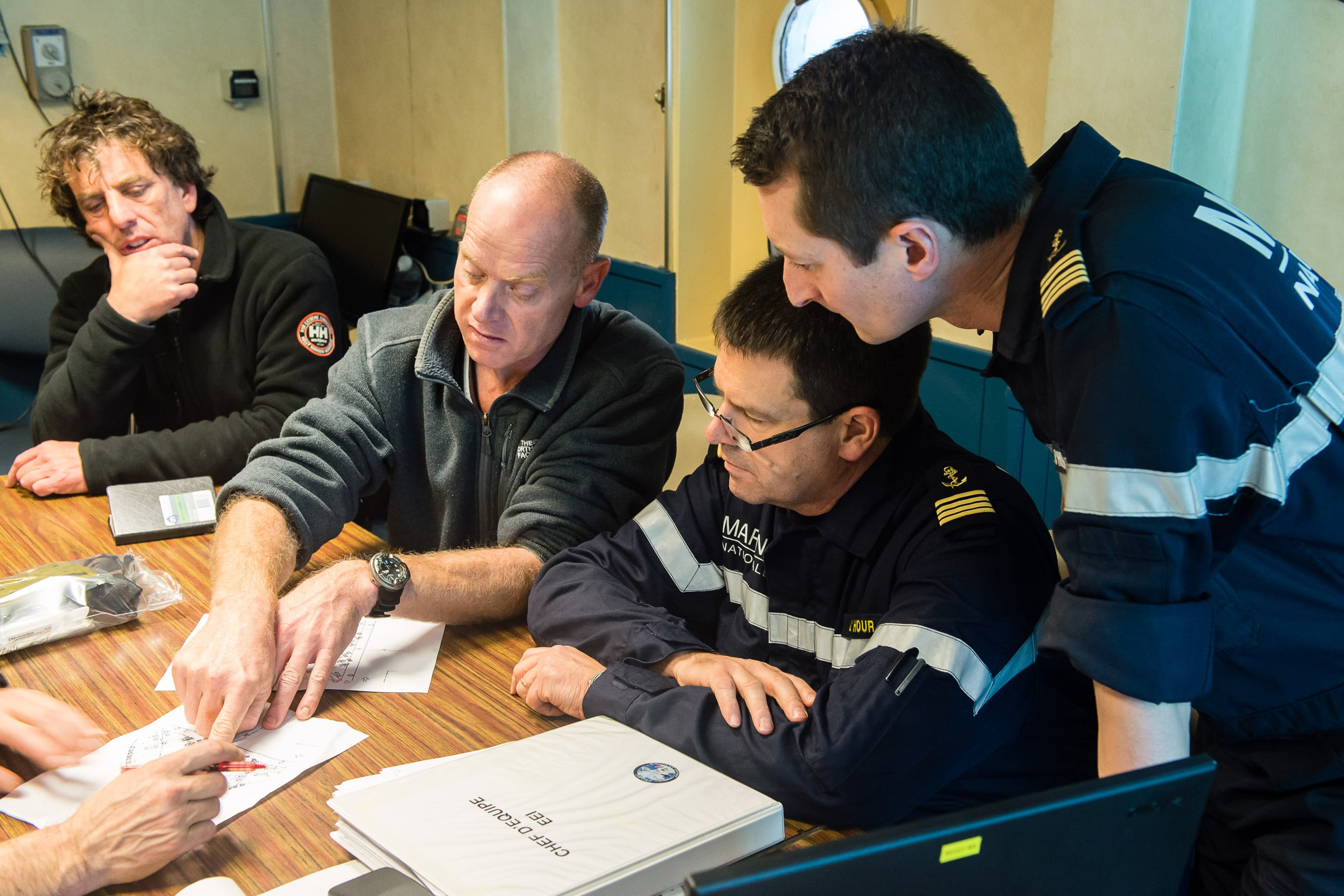

The onshore team has completed a range of preparations for the complex follow-up operation. The pumping equipment required is on its way to Bilbao. At the end of the day, the Centaurus and the Modern Express arrive at the entrance to the port of Bilbao. The Spanish authorities want to bring the ship into the port as quickly as possible. Four tugs are mobilized to help the Modern Express through the narrow channel leading to the port. However, Chris and his team prefer to wait until next morning so that the operation can be carried out in daylight. During a meeting with Spanish port authorities and representatives from various government services such as pilots, environmental services and the local fire department, Johan explains the position of the salvage team. The Spanish authorities eventually agree to the approach proposed by SMIT Salvage.

It’s like being in a large office building that is tilting right over and having to get to the ground floor from the third floor.

Wednesday, 3 February until late February

A helicopter from Bilbao takes a salvage team on board early in the morning to coordinate the towing operations at either end of the vessel. Four tugs take the Modern Express into the port of Bilbao and then complete a careful mooring operation.

There is not enough room on the quay next to the selected berth for all the equipment needed to right the ship and so the vessel is moved to where there is more space. Work then starts on drawing up a pumping plan based on the computer data from naval architect Roy. In the days that follow, the fuel is taken off board. Before the excess water can be pumped out, salvage divers have to go to work below the water line to seal off the air intakes and ventilation shafts. All 24 ballast and fuel tanks are inspected for leaks and, if necessary, repaired. The polluted water from the flooded engine room is taken to a treatment plant. Pumping can only start after calculations have been completed: the tanks have to be emptied in the right order to maintain the stability of the vessel. There are only limited facilities in the port and so the salvage team is also working on bringing in additional materials such as electrical equipment, internet facilities and fuel for the pumping equipment. Office containers and a canteen container are mobilized so that there is enough room to work and organize meetings. Various colleagues from Boskalis join the salvage team to help with the technical plans. To ensure the safety of the colleagues, SHE-Q organizes daily toolbox meetings based on the principles of the Boskalis NINA safety program.

Mission accomplished

After three intensive weeks, the Modern Express was moored on the quayside in a stable condition. “To keep the cargo in place, we righted her so that she was listing two degrees. The client is responsible for removing the cargo. The ship was now in a safe condition in a safe location, and so our mission was accomplished,” says Chris, looking back on a successful operation. “This was an excellent performance from the team. The media like to highlight the spectacular aspects of operations of this kind. That’s understandable, but it doesn’t do justice to our professional approach. The strength of SMIT Salvage is precisely that we excel in making a sound assessment of the risks on the basis of our knowledge and experience. Working safely is an absolute priority for us, however spectacular our work sometimes looks.”