In the morning of Tuesday, 23 March, the container vessel Ever Given ran aground in the Southern single-lane section of the Suez Canal. At a stroke, it completely blocked all the traffic in one of the world’s most important shipping routes. Some 18,300 vessels sail through the canal every year. Together, they carry approximately 12% of total world trade. The major economic impact meant that the blockage dominated headlines throughout the world, as did the role of Boskalis as the salvage company. In this article, we look back on this unique salvage operation.

On Tuesday, 23 March, one of the world’s largest container vessels sails into the southernmost single-lane section of the nearly 200-kilometer-long Suez Canal. The vessel heads north on its way to the Mediterranean Sea, fifth in a convoy of twenty. It is 400 meters long, the equivalent of four soccer fields, and almost 59 meters wide. It is as tall as a high-rise building and, including the cargo, it weighs more than 240,000 tons. The vessel is on its way from Tanjung Pelepas in Malaysia to the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. It has 18,350 TEU containers on board, most of them ‘forty-footers’. The canal is about 300 meters wide but it is only deep enough in the middle for a vessel as large as the Ever Given, which has a draft of almost 16 meters. At 7:40 local time, the vessel is unable to maintain its course. Its bow and stern get wedged in the sticky rock like clay on either side of the canal. The 23 Indian crew members are fortunately unharmed. The Ever Given is now completely blocking the canal.

A question of pulling hard

“It’s not uncommon for vessels to get grounded in the canal,” says Paul van ’t Hof, operations manager EMEA at Boskalis subsidiary SMIT Salvage. “The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) usually sorts things out itself with its own tugs. Usually, it’s a question of pulling hard to refloat the vessel.” But by late afternoon, the Ever Given hadn’t moved an inch. In the meantime, Boskalis has got in touch with the Japanese ship owner through its regular Japanese salvage partner, Nippon Salvage, and is asked to think about a technical solution. As a result of those contacts, Boskalis suggests sending a salvage team to look at the situation on site.

Snowball

Vessel-tracking systems and satellite imagery soon make it clear that the Ever Given is completely blocking the canal. Messages on social media indicate that the situation is serious. On Wednesday morning, 24 March, the tide of messages continues to rise and it’s not long before the phones in Boskalis’ corporate communications department are ringing nonstop. The rising demand for news is a snowball that just keeps rolling, getting bigger and bigger all the time. That evening, Boskalis’ CEO Peter Berdowski is interviewed in the Dutch current affairs program Nieuwsuur. When asked how much time the salvage operation will take, he says it could take weeks to free this ‘beached whale’ if containers have to be removed from the vessel. Numerous national and international news channels pick up that quote. The world is beginning to realize that the blockage could have a huge economic impact. The topic is suddenly the talk of the town, and so is the role of Boskalis and its subsidiary SMIT Salvage.

Only one serious shot

The salvage team boards the Ever Given on Thursday, 25 March. The team led by the salvage master Jules Martina consists of senior naval architect Alexander Gorter, naval architect Quinten Schothorst, commercial manager Jody Sheilds and salvage superintendent Peter Smits. Immediately after arrival, Martina and Smits take stock of the situation on board. Gorter and Schothorst are working on a 3D model of the Ever Given to establish a picture of the vessel’s strength, buoyancy and stability. Sheilds is the liaison officer. He manages communications with the SCA, the support team in the Netherlands and the corporate communications team. The salvage team and the support team in the Netherlands soon realize that heavy tugs are needed on the south side, while all the SCA’s equipment is located to the north of the vessel. “We knew one thing for sure: an exceptionally high tide was expected early the next week,” says global operations manager Thijs van der Jagt, who coordinated the salvage operation on shore in Egypt.”That was going to be our best shot – and perhaps the only serious shot for the time being – to refloat the Ever Given. If pulling wouldn’t work, we had a Plan B and Plan C up ready: removing the soil from below the massive vessel or removing cargo.”

Sixteenth floor

During the days that follow, a lot of work goes into calculations to determine the concrete details of various options at the same time. “Which meant that we weren’t just working on the most obvious solution, Plan A – in other words pulling the vessel afloat – but that we were also preparing for the possibility that a Plan B or even a Plan C could be needed,” says Van ‘t Hof. Thanks to intensive efforts focusing on Plan A, contacts are established in the region with two heavy seagoing tugs, the ALP Guard and the Carlo Magno. They are available to provide assistance but they will have to sail to Egypt from the Indian Ocean against strong headwinds. Which means they won’t arrive until Sunday or Monday. Plan B involves using dredging technology to free the vessel, drawing on the knowledge and experience of colleagues from Boskalis’ Dredging division and locally available equipment from the SCA, among others. “If that didn’t get the vessel off, we would have to switch to Plan C: unloading a large number of containers to reduce the weight of the Ever Given,” explains Van ‘t Hof. “That would have been an enormous job. The top containers were on the sixteenth floor of what was effectively a high-rise building. So getting them off was going to be quite a challenge, even more so in the windy conditions at the time. But fortunately, we could fall back on our wide-ranging logistical and technical expertise – if there is one company in the world that has the equipment for an operation like this, it’s Boskalis.”

Experts

A large group of colleagues working both from home and at the office, and the salvage team, move heaven and earth to work out the three scenarios in detail. A range of Boskalis experts travel urgently to Egypt to keep the execution of the various plans on track. And the results are impressive. In order to flush out the soil under the Ever Given for Plan B, it is decided to use a cutter suction dredger from the SCA as a pump. The required pipelines and other equipment are hastily mobilized in twenty-four containers from Alexandria, where Boskalis has recently completed a project. In order to execute Plan C, contacts are established with suppliers of large transport vessels and colossal cranes. Calculations are being made on all fronts for this gigantic operation, which could include removing hundreds of containers.

A first attempt

On Sunday night, with assistance from the crew of the Ever Given, the salvage team connects the towlines of the heavy tug ALP Guard to the bollards of the container vessel. While about ten pushers and tugs are at work on the north side, the ALP Guard and a second lighter tug on the south side try to pull the stern of the ship towards the middle of the canal. After about an hour, they manage to get the stern to move. On Monday morning the vessel has moved about twenty degrees into the center of canal. The bow is still stuck on the east bank but the stern is now more or less in the middle of the canal. But during the course of the morning, the current in the canal changes direction. The strength of the incoming current is now such that the two tugs can’t keep the Ever Given in place. The vessel slowly returns to its original position blocking the canal. Once again, the Ever Given proves to be an awkward customer and it is now also listing about four degrees to the port side.

Water pressure

When the spring tide in the Suez Canal ebbs early in the afternoon, the direction of the current also changes. It is now flowing from north to south, and the speed of the current will peak in the late afternoon. So this is expected to be the best opportunity for the refloating operation. “We improved our chances by pumping more water, approximately 5,000 tons, to the stern section of the Ever Given using the ballast system,” says Gorter. The repairs made by the salvage team have reduced the risk of leaks in the bow and made buoyancy more predictable. The strong current in the canal moves an enormous amount of water. The normal flow in the canal is now almost completely blocked by the Ever Given, and the fast-flowing body of water has to find a way through. It pushes against the hull with enormous force. The ALP Guard and the Carlo Magno manage to pull the stern of the ship to the middle of the canal and shortly thereafter the bow of the Ever Given comes off the bank inch by inch. The vessel starts to turn. Tugs blare their horns for minutes; enthusiastic crew members try to compete with shouts of victory. After these joyous moments, the Ever Given is towed to the Great Bitter Lake to anchor there.

But the salvage team, still has work to do. They stay on board and follow the fixed procedure for almost every salvage operation: their work isn’t done until the vessel is in a stable condition in a safe location. They report to their colleagues from the onshore team in Egypt on Tuesday evening, who give them a hero’s welcome. For Boskalis, the salvage operation and the company’s involvement with the blockage are now over.

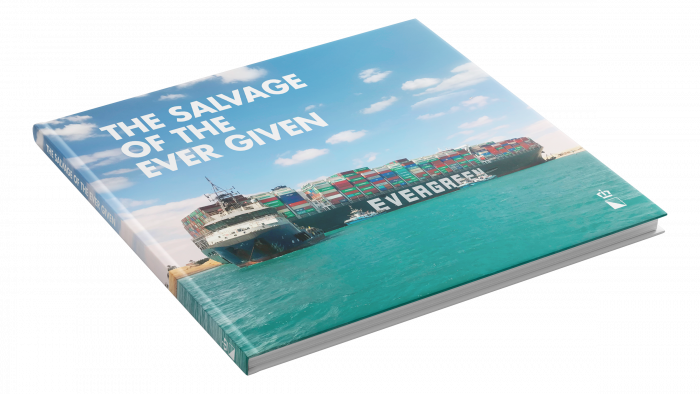

Book about the salvage operation

Boskalis recently published a book that offers a look behind the scenes of this unique salvage operation. Based on interviews with a large number of people involved, combined with various photographs, the book paints a chronological picture of the various activities that took place on board the stranded vessel by the salvage team, the support team on shore in Egypt as well as the Boskalis offices. The book can be ordered from the Boskalis shop.