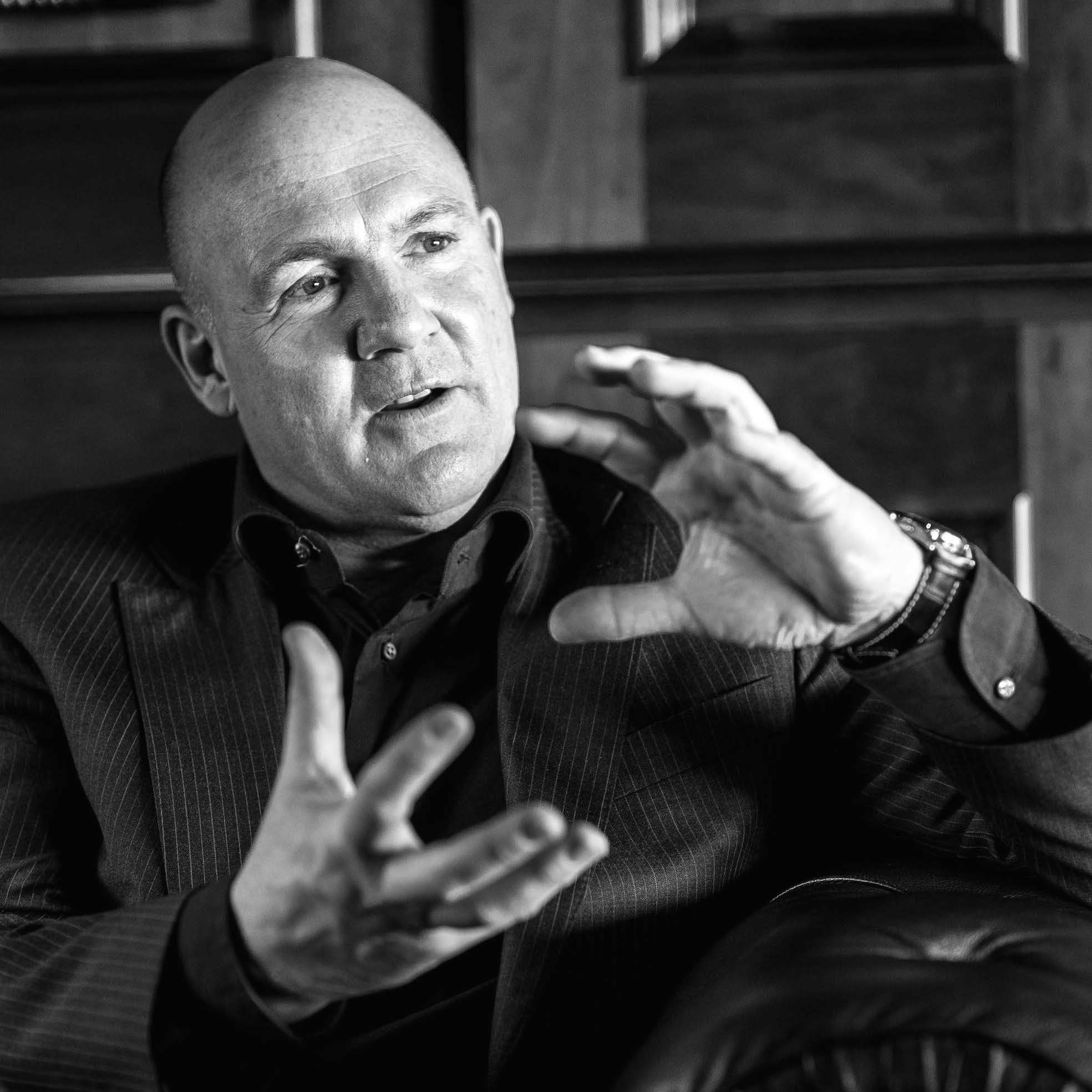

In an exclusive interview astronaut André Kuipers illustrates why you should never stop exploring

Cosmonaut — as he prefers to be called — Dutchman André Kuipers is one of the few Europeans that have been to space, and even more remarkably, he has been twice, clocking up 204 days in two extraordinary missions. In an exclusive interview André talks about his motivation to broaden his horizon and soar into space. Surprisingly, he says there are many similarities between the work of space pioneers and that of Boskalis…

The initial spark for André came when his grandma bought him some science fiction books and he was also inspired by watching the TV documentary series Cosmos and IMAX movies from the US Space Shuttles. “This started the dream. It was adventurous, beautiful and also very useful. I worked as a medical doctor and somehow wanted to advance human kind. It was this combination of the three factors that made me want to go to space.”

André, the Boskalis Magazine is called Creating New Horizons, could you explain if this experience changed your horizons?

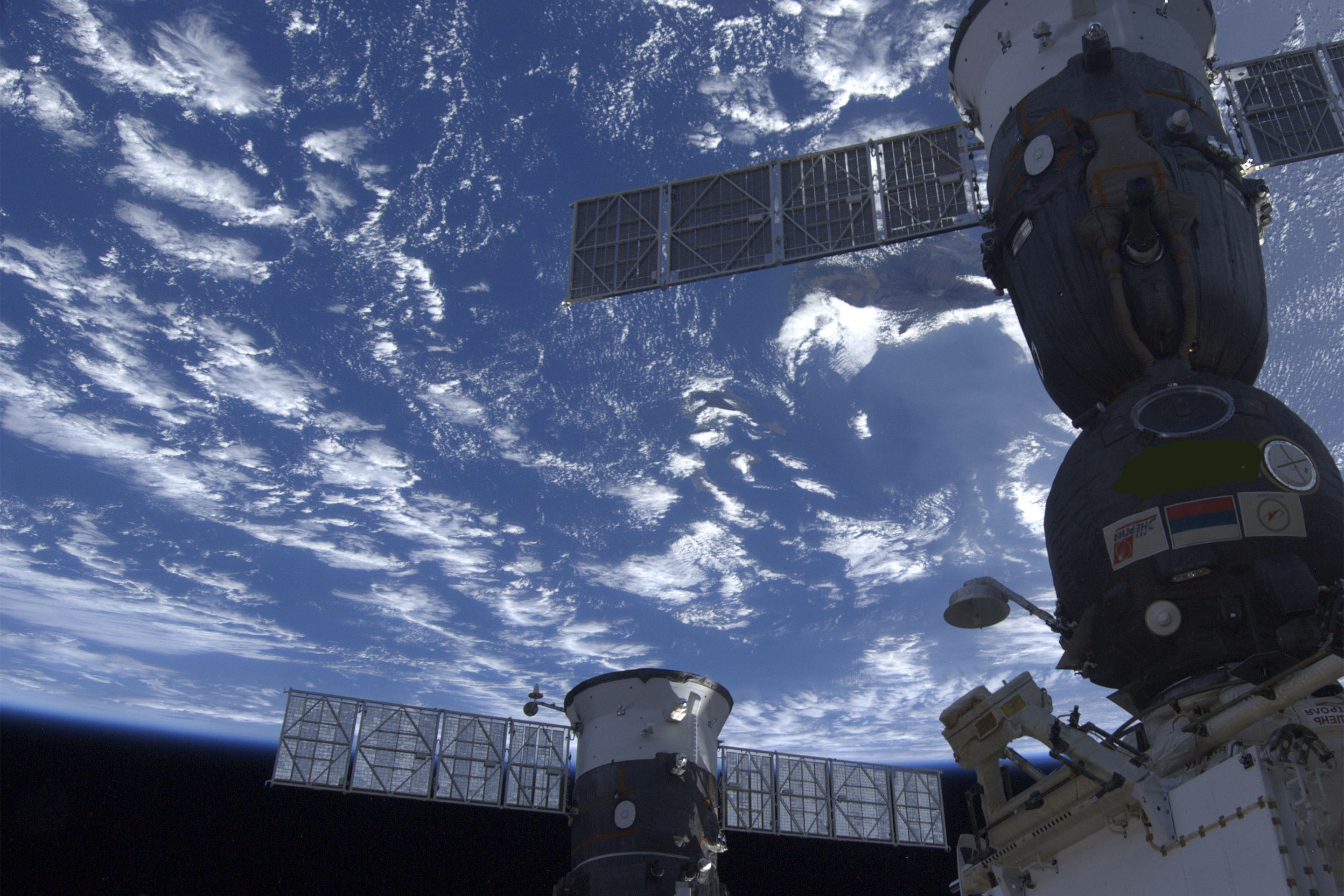

“The International Space Station (ISS) circles the Earth very fast (taking just 90 minutes). You see incredibly fast sunrises, the Northern and Southerns lights, a comet and feel part of it. I call it a ‘cosmic feeling’. We are part of a moving system with everything turning around each other. Yes, my horizon was enlarged by my experience in space but at the same time, I worry about how limited the planet is, it is not endless.”

What are typical ‘cosmonaut characteristics’?

“You have to have a lot of motivation. From preparation to the execution of a space mission, there are some four years training involved for half a year in space. The long lead times can be frustrating. Also things go wrong and everything takes longer, there are always people in front of you.” (Referring to the many years it can take when you await to be chosen for a mission.) “Perseverance is crucial, you have to hold on and keep going.”

How important is teamwork when you are in space?

“Space flight is all about international cooperation. For example, I work with at least 20 different nationalities at the European Space Agency (ESA). The Netherlands is part of the ESA, which itself is a partner in the ISS in which Europe participates for 8%. We share the space station with the US, Russia, Canada, Japan and other European countries.” While Boskalis works offshore and in remote environments and André works ‘off-planet’, for both, teamwork is crucial, he emphasizes. This is particularly the case when it comes to work onboard the ISS.

“We are all entirely dependent on each other. ‘Astronaut to astronaut’, with the technicians and engineers in the control centers, we all help each other out to achieve a successful outcome.” Additionally, there are a lot of delicate negotiations, he stresses regarding both cultural factors and technology. For example, what language is going to be used, inches or centimeters, which voltage, fire extinguishers (CO2 or water-based) etc.

If Boskalis still exists in 100 years, I would not be surprised if it is involved in a related business in space. Why not?

Undoubtedly, the one thing all space travellers have in common — and something that is also at the foundation of Boskalis — is that safety is always first?

“Safety is always the most important factor during training, preparation and execution.” He stresses that safety absolutely has to be at the forefront of your mind. “It is all too easy to get lured into a false sense of security. You feel very safe onboard the ISS. There is a normal temperature and air pressure — you forget that there is only a thin layer of aluminum separating you from the vacuum of space.”

Once making the most amazing journey of your life and reaching the space station — safety is immediate. “The first thing you do on arrival is quickly wave to the TV cameras and then you take the space station safety inspection tour and immediately learn how to close the hatches quickly. Normally, you would do this when your feet are firmly on the floor during training. But now the hatch is floating as are you, and it takes an effort to get it down. And you have to fix yourself in order to quickly close the hatch. You find out where oxygen masks are, fire extinguishers, escape routes, what happens if the lights go out …”

And just like when visitors arrive at the Boskalis headquarters and see a large video screen outlining its NINA safety initiative, which encourages people to come forward with suggestions about any safety improvements, the ISS also has a very open safety culture. “Positive criticism is encouraged about any safety improvement.”

Assessing, monitoring and preventing risks is essential to our work. That will be no different from a stay in space. How are astronauts being prepared for this?

“Preparation is extensive and training includes everything from disaster emergency drills, computer failure, radar systems dropping out to ammonia leaks, short circuiting and what to do if space debris threatens to hit the ISS.” He estimates that he probably hasn’t used 80% of his training because most of it involves these ‘what if’ scenarios.

In his typically modest way, he plays down the risks of space travel, adding that the offshore industry has many similarities: a dangerous environment, with people working a long way from home in very harsh conditions. “I always know that if I can reach the Soyuz capsule I can get home — I might land in the middle of the Pacific or Siberia in minus 40, but I can get back.”

He describes the return journey from the ISS and re-entry as the ‘most exciting’ part of the project. For André ‘most exciting’ is perhaps a euphemism for what most people would describe as petrifying!

“Being in the Soyuz capsule to return is similar to squeezing three tall men into the front of a Fiat 500”, he laughs. There are several critical moments, he explains, one of which is when they have to brake after the Soyuz has undocked from the space station. A small rocket has to decelerate the capsule enough to lower the orbit so they can get into the atmosphere; after 20 minutes they hit the air, when in effect they are a fireball shooting through the atmosphere. And then the heat shield has to do its job. Another key moment was when the parachute had to open at a 10 km altitude followed by the rough landing in Kazakhstan.

The strategic drivers behind Boskalis’s business are the growth in global trade and energy use, climate change and the increase in world population. When looking down on the earth is the human footprint very clear to see?

“Absolutely. You see the impact of deforestation, soil erosion, air pollution and the contrails from aircraft. But the city lights are dominant. There are some dark spots in Australia and Greenland but not many in Europe or the US East coast.”

You see incredibly fast sunrises, the Northern lights, a comet and feel part of it. I call it that ‘cosmic feeling’.

Large infrastructure projects can also be seen such as the huge port expansion project in Rotterdam - Maasvlakte 2 - in which Boskalis is playing a key role, responsible for dredging and the construction of 2,000 hectares of new land. André knows Maasvlakte 2 well having photographed it from space and as a Dutchman the site fills him with pride. “From space The Netherlands really stands out in Europe, because it is possible to see how the Dutch have managed and protected the land, with the innovative Sand Motor and hundreds of dikes and canals”, he says.

Satellite picture of the west coast of The Netherlands by the Sentinel-1A satellite, which was launched in April 2014. On the left Maasvlakte 2 can be seen and just above the Rotterdam port extension the contours of the Sand Motor are pictured.

For a couple of years now Boskalis is involved in activities with regard to plastic soup in the oceans. Could you see the phenomenon plastic soup from space?

Although André could not see any ‘plastic soup’ in the oceans directly from space since most floats under the surface, he adds, that there is certainly plenty of space waste. “Emergency drills for a leak in the ISS due to a hit with space debris is an important part of a cosmonaut’s training and a very necessary one.” He points out that there are at least 17,000 pieces of space debris bigger than 10 cm that are tracked by radar and tens of thousands more that you can’t see.

What runs through your mind when you are soaring above the earth contemplating the impact humankind has on the planet?

“While it is great to see things happening we do have to be careful”, he points out, saying that sometimes he gets a ‘claustrophobic feeling’ for the planet. “When viewing the earth you feel it is fragile and limited. It feels like a living cell, when you see the marble blue next to the darkness of space… earth feels very vulnerable.”

Although he is worried about the earth and its valuable resources, he is “absolutely optimistic about the potential for young people coming up with ‘brilliant smart new ideas’ and the endless potential of technology. If we look back at the Middle Ages most of today’s technology would be considered witchcraft”, he quips, “think of mobile phones, electric cars with a range of more than 400 km, renewable energy…”

So you are confident that humanity will continue its endless drive to explore new horizons?

“Yes, but to create a sustainable world R&D is vital”, he stresses. “And companies like Boskalis, which continue to innovate and push the technology boundaries, play a crucial role. Innovation is a must”, he asserts. “If Boskalis still exists in 100 years, I would not be surprised if it is involved in a related business in space. Why not?”

And when you have been to space twice, are there any career challenges left?

Nowadays André is active for the ESA, the Netherlands Space Office, several ministries and the education sector in the context of the socalled Techniekpact, to motivate children to choose for technical studies. André also spends much time representing the World Wildlife Fund.

Finally, André is a third space mission likely?

“I wouldn’t mind going again, but ESA has only one astronaut in space per year, in average. I want to give way to the new generation. Besides that, I promised my family not to soar into space again – it is not the actual mission but the years of intensive training that are a big burden to social and family life.” However, you get the feeling there is a ‘but’ coming on … “unless it is going to the moon…”