Where nature, technology and art meet

Kinetic sculptor Theo Jansen uses the forces of nature to create his magical Strandbeests (Beach animals). Whilst Boskalis works with sand and water to protect and replenish the coastline, Theo originally created his Strandbeest to gather sand and rebuild the dunes through wind power. Then evolution took over…

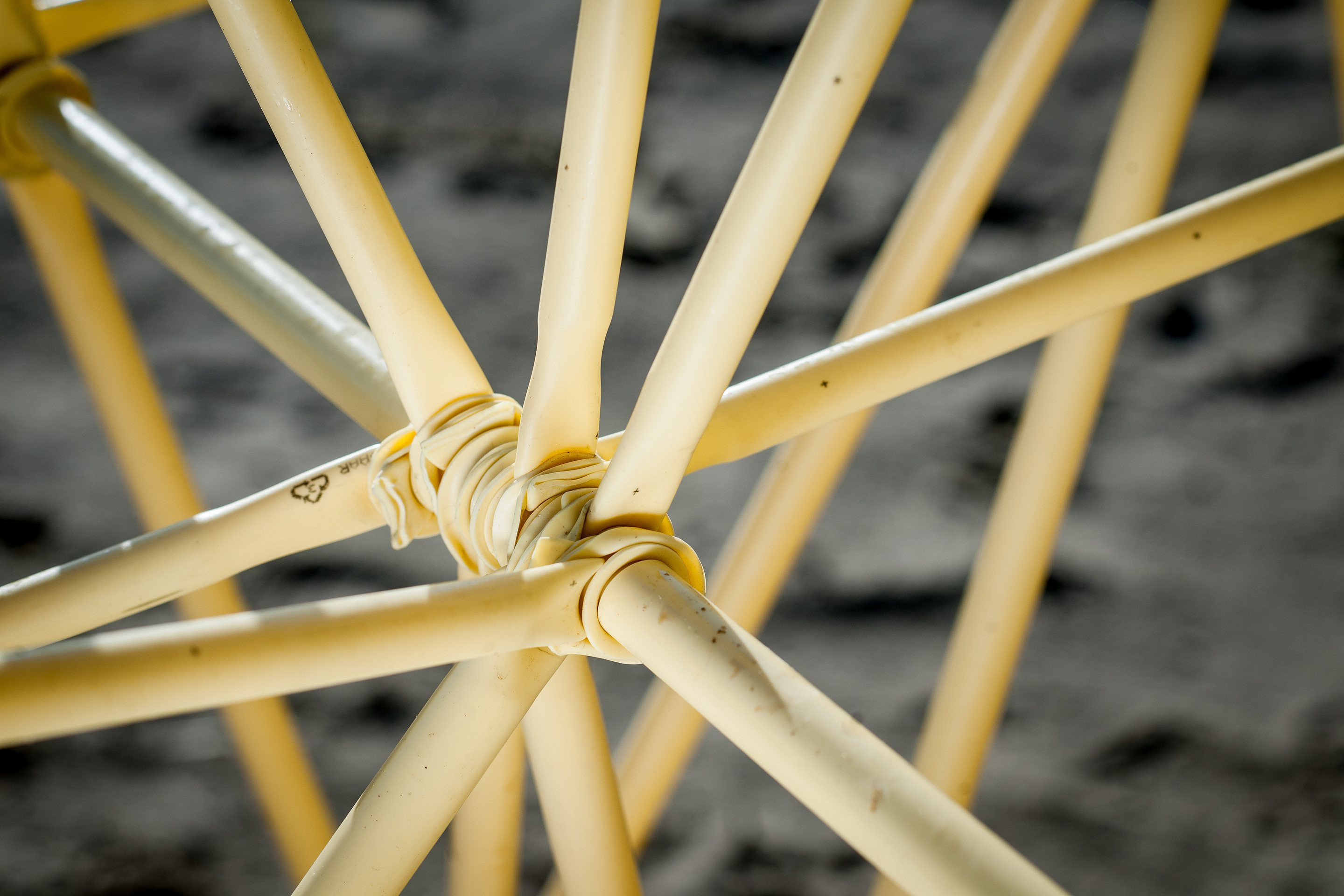

Theo Jansen has been creating ‘wind-walking’ kinetic sculptures since the nineties. This new form of ‘life’ was a rudimentary breed at first. It has slowly evolved into a generation of magical creatures able to respond to their environment. He calls them Strandbeests. Constructed as intricate assemblages from piping, recycled plastic bottles and wing-like sails, Theo’s Strandbeests are constantly evolving and have adapted excellently to their beach environment. His work exemplifies the meeting of nature, technology and art.

How did you originally come up with the idea of creating a Strandbeest?

“It is in our Dutch genes to try to save the country from flooding. Continuously fighting the elements. It is natural for us to look at the roots of life. After reading The Blind Watchmaker by Richard Dawkins, which centers on the theory of evolution by means of natural selection, I came up with the strange idea of making new life forms that could gather sand and rebuild the dunes using wind power. Later that day, passing a big DIY shop, I saw some hollow, yellow plastic tubes (the type used for electrical wiring) and the idea came to me of spending a year working with the tubes.”

The first Strandbeest was born — the Animaris Vulgaris. “It could only lie on its back and could not even stand on its feet. It had three limbs and was very uncomplicated.”

But then came the evolutionary breakthrough?

“Yes, during a very bad night’s sleep in 1991 I was thinking about the spine of such an animal and the leg movement. It was apparent that the ‘toe’ had to have a certain curve and a flat bottom. When you look at animals, you see that the legs cannot spend too much time in the air; they have to go down as quickly as possible to maintain balance. It is the same for the Strandbeest. Then it came to me; a genetic algorithm was needed to get the right proportions for the legs!”

Although known for his kinetic sculptures, Theo studied physics at one of the world’s top technical universities, Delft University of Technology, for seven years. Theo turned to his scientific background and, using an old Atari computer, he considered millions of possibilities (random lengths of tube) for the ideal leg shape. This resulted in 1,500 different combinations of curves.

“The Atari worked away for weeks, if not months, day and night. Eventually it generated my ‘13 holy numbers’ or in other words, 13 lengths of tube. This was the DNA code for the Strandbeests. This led to the second animal — Animaris Currens Vulgaris. Now it could walk.”

Why did you give the DNA away?

(Theo published the 13 holy numbers on his website back in the nineties)

“Without knowing it, all the people who use the DNA to create an animal are taking part in the reproduction and evolution of the species,” he laughs. “Thousands of students wanted the code, of course, just for fun mostly. There are a lot of creatures out there now, from Japan to the US. They have also been made into bicycles and even a type of Segway.”

He stresses that he always welcomes new ideas for interesting applications.

“They are multiplying through the Internet and with 3D printing it is out of control. There are probably a lot of mutants walking about. This is real evolution; the animals are not necessarily walking on beaches but they are pretty good at surviving on bookshelves.”

Without knowing it, all the people who use the DNA to create an animal are taking part in the reproduction and evolution of the species

How does the creative process work?

“One animal is created each year and after that they are declared extinct. So the evolutionary process is very fast. Typically, a new one starts life in October. I wake up with an engineering idea then jump on my bike and go to my studio. Crucially, though, there aren’t the same restrictions an engineer would face. The tubes may correct me and push me in a different direction. There is a plan from A to B but the tubes don’t allow me to realize the plan. At the end of the day I may leave depressed but then another idea emerges. It is a capricious path, completely unpredictable. In the spring the new species is taken for trials on the beach. They evolve during the summer and I declare them dead in winter. The process is completely organic. And when it doesn’t work they go to the ‘bone yard’ and return ‘home’.”

Were there ever any challenges that you thought it was impossible to overcome?

“I always strive to push the boundaries of what we know and what seems possible but, of course, there were some challenging moments. When the first animal was on its back, people did wonder how could anyone think this was going to go somewhere. But I just believed in it — 99% because I am quite naïve and maybe a little bit pretentious. I just thought: this is going to work.”

Most people are touched emotionally by the creatures, there have even been people in floods of tears

Your amazing beach animal creations are an inspiration for people all over the world but what inspires you?

“Life inspires me; it is such a miracle. The beach was where I was born: pretty much coming out of the sea in Scheveningen (near The Hague). The beach is inspiration enough, especially the clouds, the sea… Most people are touched emotionally by the creatures, there have even been people in floods of tears.”

Theo is rather perplexed by people’s response sometimes, explaining that he doesn’t deliberately set out to create beautiful animals and evoke such strong emotions. Creating his Strandbeests through an evolutionary engineering process is what drives him.

Engineering is clearly an important part of your work. Are there any similarities between what you do and the work of Boskalis engineers?

“I believe engineers can now be artists as well. In the past, to build a bridge, they have not been able to ‘play’ with material. They have a responsibility as engineers — a bridge must stay in place and do its job. Engineers were not allowed to be artists. But now, with sophisticated computer simulations, they can make hundreds of bridges and they have the luxury of playing with designs.”

Is the idea of replenishing the dunes ever likely to be realized by your animals?

“The creatures can hold on to sand. But I think my rivals (referring to Boskalis) have beaten me to the large sand replenishment and reclamation projects,” he smiles. “Boskalis has outpaced the evolution of the creatures by a big margin, and it too uses the forces of nature, like with the Sand Motor.”

Eventually, I want to put these animals out in herds on the beaches, so they will live their own lives

What is the next stage of the evolutionary process — the following new horizon?

“The next natural evolutionary step will be for the animals start to ‘make their own decisions’, so they can work on soft and hard sand. Self-propelling Strandbeests have a stomach. This consists of recycled plastic bottles that enable the animals to store air pressure and use it to drive them in the absence of wind. This year, for the first time, the 42-foot-long Animaris Suspendisse walked with the wind. When there was a hard wind, parallel to the coast, the Strandbeest could walk around 5 kilometers along the beach in about 30 minutes to an hour. However, I still have some work to do on maintaining its course, and I may need to invest in a four-wheel drive to bring it back”, he quips.

Theo’s more sophisticated creations are able to detect whether they have entered the water and walk away from it. One species will even anchor itself to the sand if it senses a storm approaching. “Eventually, I want to put these animals out in herds on the beaches, so they will live their own lives. It is quite amazing that they have already been walking for 24 years. They are walking the path of evolution.” Watching a herd of them crossing a windswept beach would certainly be a sight to behold…